Australia’s unfinished Square Kilometre Array telescope is at risk of having its sensitive space observations distorted by Starlink, with new research showing the low-orbiting satellites are leaking low-frequency radio waves.

A study by Curtin University researchers detected the constellation of low-Earth orbit satellites emitting unintended signals in the frequency band used by what will become the world’s largest low-frequency radio telescope.

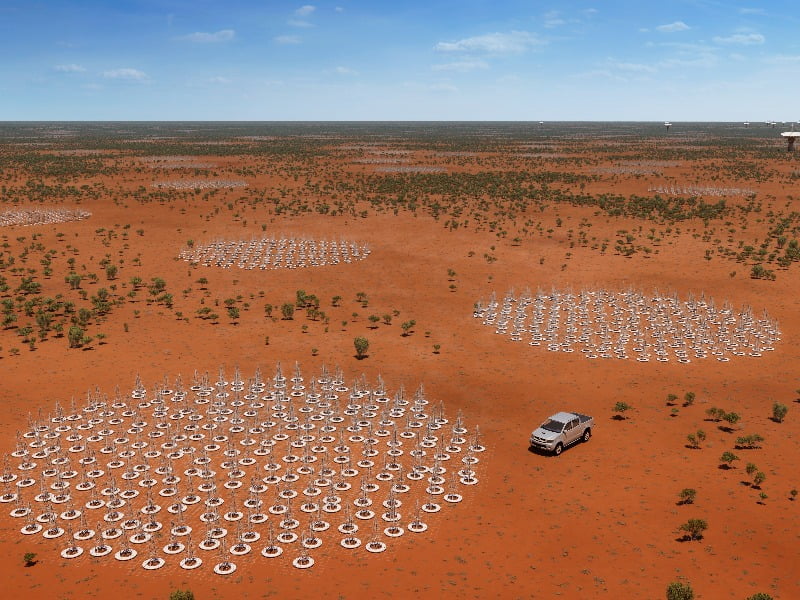

SKA-Low, which remains under construction, is one of two arrays that will be built as part of a project first conceived in the 1990s. The other array, SKA-Mid, is located in South Africa.

The telescope operates in the 50-350 MHz frequency range that is primarily used for space observation, while South Africa’s uses the 350 MHz to 15.4 GHz bandwidth also used by LEO satellites.

Scientists in South Africa last month sounded the alarm over the issue, and began lobbying the government to introduce licence restrictions to reduce the impact on observations in certain frequency ranges.

But researchers from Curtin University’s node of the International Centre for Radio Astronomy Research now believe Starlink’s 7,000 LEO satellites could impact discovery and research out of Australia.

The study, published on Wednesday, detected “more than 112,000 radio emissions from 1,806 Starlink satellites” over a four-month period, including at low frequencies, such as between 73 and 74.60 MHz and 150.05 and 153 MHz.

“Some satellites were detected emitting in bands where no signals are supposed to be present at all, such as the 703 satellites we identified at 150.8 MHz, which is meant to be protected for radio astronomy,” PhD candidate and study lead Dylan Grigg said.

“Because they may come from components like onboard electronics and they’re not part of an intentional signal, astronomers can’t easily predict them or filter them out.”

Across the 76 million images collected and analysed using a prototype SKA station, located at the Murchison Radio-astronomy Observatory in outback Western Australia, a Starlink satellite was detected in almost 30 per cent of images.

“Starlink is the most immediate and frequent source of potential interference for radio astronomy: it launched 477 satellites during this study’s four-month data collection period alone,” Mr Grigg said.

Curtin Institute of Radio Astronomy executive director Steven Tingay, who co-authored the study, said that while Starlink is not violating current regulations, there is scope for improvement to help avoid interference with research and discovery.

“Current International Telecommunication Union regulations focus on intentional transmissions and do not cover this type of unintended emission,” Professor Tingay said.

“Starlink isn’t the only satellite network, but it is by far the biggest and its emissions are now increasingly prominent in our data.

“We hope this study adds support for international efforts to update policies that regulate the impact of this technology on radio astronomy research, that are currently underway.”

Professor Tingay added that for the SKA to help answer some of the biggest unanswered questions in science, such as how the first stars formed, it would need “radio silence”.

“We recognise the deep benefits of global connectivity but we need balance and that starts with an understanding of the problem, which is the goal of our work,” Professor Tingay said.

Do you know more? Contact James Riley via Email.