From grey zone coercion to regional surveillance competition, the Indo-Pacific is now in live contest. Yet our national innovation posture is not structured to mitigate emerging risks or leverage strategic possibilities. Innovation is now a national imperative, underpinning Australia’s security and safety as much as economic prosperity. Without a stronger innovation engine, Australia will struggle.

To meet these needs, Australia should develop, field and scale technology to pick up pace, overcome fragmentation and shift from promise to delivery. Without this, our most capable innovators and entrepreneurs will continue heading offshore in search of faster capital, clearer pathways and more strategic demand.

Home Affairs Minister Tony Burke has rightly framed the concept of ‘national safety’, distinct from ‘national security’, as encompassing counterterrorism, cyber threats, foreign interference and infrastructure protection. This recognises that national safety is not a passive derivative of national security but a parallel priority.

It means protecting Australians, our economy, and our way of life from a spectrum of risks: economic coercion; cyberattacks; disinformation; unfair market manipulation; supply chain disruption; and climate shocks. In a contested world, the ability to endure and recover is just as important to strategy as the ability to deter and counter.

National safety innovation means investing in secure supply chains, robust public infrastructure and services, digital and societal resilience, and technologies that protect civil society and economic sovereignty.

Yet innovation in Australia is still framed almost entirely in terms of productivity—jobs, growth and exports. Productivity alone is insufficient, particularly when decoupled from environmental, social and governance standards. Safety and societal resilience should be embedded within how we define responsible, domestic innovation.

Despite world-class talent and research capability, Australia underinvests, under-prioritises, and under-coordinates. Our spending on research and development is 1.7 per cent of GDP, well below the OECD average of 2.7 per cent. Peers such as the United States (3.5 per cent), Japan (3.3 per cent), Britain (2.9 per cent) and Singapore (1.9 per cent) all invest more. China invests 2.7 per cent, while Israel leads globally, with more than 6 per cent.

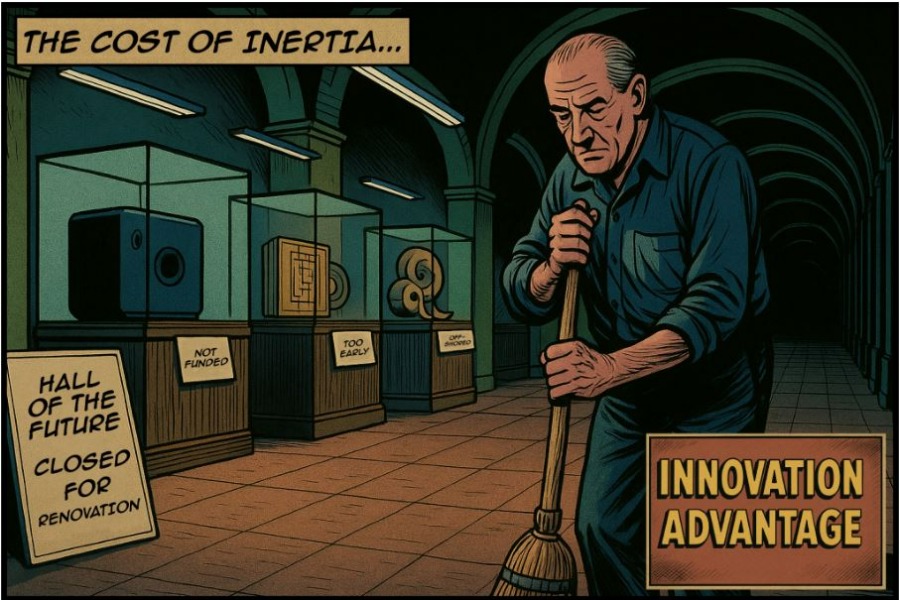

At the same time, Australia ranks 105th out of 132 countries on the Economic Complexity Index – the lowest among OECD nations, down from 55th in 1995. Venture capital favours low-risk plays over national consequence. Public support programs are dispersed across departments with no common objective. There is no operating model that ties innovation to real-world capability outcomes.

This shortfall is most visible in the context of AUKUS Pillar Two. Built to accelerate capability in quantum, AI, cyber, and autonomy, the initiative assumes each partner can deliver at speed. But Australia’s contribution remains limited. Our research leads in some areas, but our deployment lags in most. Without the means to prototype, verify and scale secure technologies onshore, we will remain dependent on others.

From secure identity systems to critical infrastructure sensors, our digital backbone depends on foreign components we neither design nor manufacture. In a crisis, those dependencies may not hold. Even in the peacetime, they limit what we can field, certify or export without compromise.

Policy coordination for some of the fastest-moving threats sit within Home Affairs. The department covers immigration and borders, national security and resilience, and cyber and infrastructure security.

There is now an opportunity to connect that remit to innovation and economic security. Australia’s lead department for many high-speed, high-consequence risks is not afforded a formal mechanism to shape upstream R&D pipelines, create market signals or drive downstream adoption.

This is because Australia’s broader innovation system reinforces a structural disconnect. Research is governed by one department, commercialisation by another, and procurement by a third. Speed and accountability are lost in the gaps. Even the Advanced Strategic Capabilities Accelerator, built to speed up Defence innovation, is still maturing and has not yet extended its reach to other high-risk agencies.

What’s needed is a delivery posture: a model where departments such as Home Affairs issue challenge-based calls; early-stage technologies are met with secure prototyping environments; and readiness is judged by deployability and trust, not citations or pitch decks.

This is not about centralising control. It’s about whole-of-society convening and using existing tools such as procurement, investment mandates, and standards policy in new combinations. It is about empowering mission owners to shape the ecosystem, not just respond to it, and recognising that innovation is strategic infrastructure.

Australia has the skills and research. It has early-stage companies building real capability in areas such as secure computing capacity, edge networks, post-quantum cryptography, and automated threat detection. But most of these will not scale unless the system shifts.

Innovation inertia may not carry immediate political cost. But in a future where threats move at machine speed, and trust is won or lost at the edge, our current posture will not hold. So, if the risks are clear and the assets are here, why are we still watching capability slip through our fingers?

This article was originally published in the Australian Strategic Policy Institute’s The Strategist. You can view the original here.

Do you know more? Contact James Riley via Email.