Australia has the talent and the capital to turn its science innovations into economic advantage at scale, according to the experts leading the current commercialisation push.

But a culture shift to genuine collaboration and incentives to direct the capital to where it’s needed remain key barriers.

At a CEDA event on Friday, the people at the commercialisation coalface explained the challenge, what is already working, what isn’t, and how Australia can duplicate the early success stories.

Science and Technology Australia (STA) chief executive officer Misha Schubert said world leading frontier science had put Australia “on the cusp of a golden opportunity” but the nation needs to build a better bridge over the valley of death to reach translation and commercialisation.

“Too often in our country in recent history, when someone has made that breakthrough both the seed capital to get that innovation further along that pathway to develop it to a fully-fledged entity and the skills and drive of our entrepreneurs amongst the science community haven’t always been in a neat linear fashion along that line,” Ms Schubert said.

The solution is more backing for scientists at the seed level, Ms Schubert said – STA has called for a multibillion dollar research translation fund — and arming Australia’s scientists, entrepreneurs and technologists the skills and the knowledge about how to commercialise products.

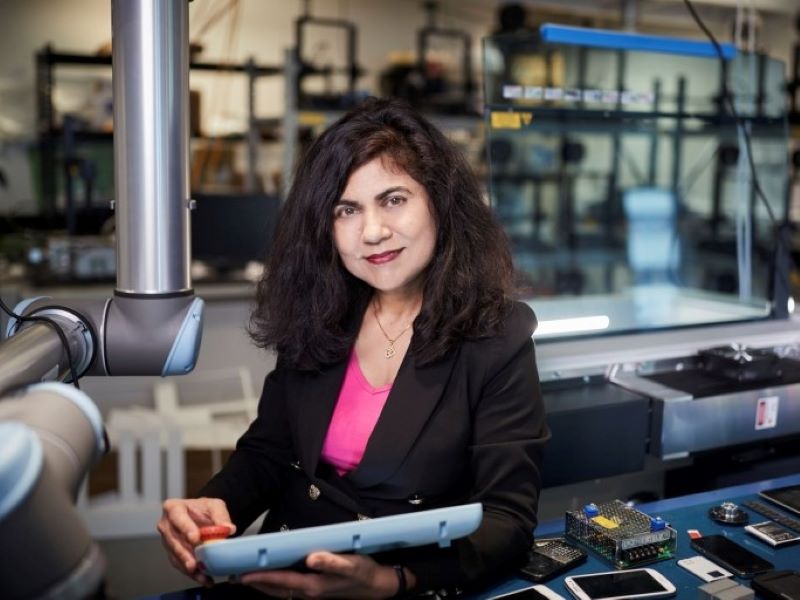

There are already examples to follow for what Ms Schubert and STA call these ‘bench to boardroom scientists’, including fellow panellist and UNSW Scientia Professor Veena Sahajwalla.

Professor Sahajwalla, a world-leading expert in the field of recycling science and inventor of ‘green steel’, has taken her frontier science along the commercialisation track with “MICROfactories”.

The buildings with a handful of staff use the scientist’s proprietary techniques like thermal isolation, to “unpick” complex structures. For example, old mattresses destined for landfill can be broken down and recycled into ceramic tiles, while manganese and zinc can be extracted from dead batteries and used in 3D printer filament.

“The realities are that a lot of our resources that we have, we know that there is value in it. It’s about harnessing that value,” Professor said at the CEDA discussion.

“So this is a beautiful sort of case of that interface between science, technology, commerce, and then all of those new jobs that can come out of that.”

While the science behind them is decades in the making, it’s been a relatively rapid translation for the MICROfactories since the first was piloted within UNSW in 2018. Commercial versions are now operating, including in regional areas.

“It is absolutely feasible and doable when we’ve all got these values, those shared values, that are aligned,” Professor Sahajwalla said.

Aligning the values means knowing your partners, she explained, including the practical problems they are trying to solve and scientists seeing “how translation and impact can actually be delivered”.

“It’s really [about] recognising each other’s ‘businesses’, if I can call it that, and each other’s motivation. [But] it’s not to say that we all have to quit our day jobs and often go and do other things.”

Professor Sahajwalla said her sabbatical to a US steel plant, for example, was critical to both her scientific work and its later commercialisation.

“Nothing beats having that production floor experience — engaging and talking that language where you can now understand each other’s journeys. I think that’s important…Should I just take the approach of saying, ‘here’s a paper, here’s a patent, go and read it?’ [No], that’s not enough,” she said.

As for funding the bridge over the valley of death, the problem is not necessarily a lack of risk tolerance or capital, according to IP Group Australia managing director Michael Molinari.

Mr Molinari, whose organisation was set up to fund projects that bridge the gap between frontier science and commercialisation, said the problem in Australia is where the capital is allocated in the Australian economy.

He said the UK provides a useful example of how to redirect it, with its Enterprise Investment Scheme program.

“This is a program of tax incentives aimed at encouraging individuals to invest in high growth technology companies. It’s a fairly significant tax advantage,” he said on the panel.

Over the last five years, the UK program has attracted over £1.5 billion from investors each year and its latest expansion into knowledge intensive stream is targeted at university spinouts, he said.

“That’s a program that has shifted the needle,” Mr Molinari said.

“It has shifted large amounts of capital from one part of investment in the economy and focused it on an area of national focus for the UK Government. And I think there’s something that we could learn from that.”

The huge capital in Australian super funds is also a potentially powerful level for local innovation, Mr Molinari said.

“If you really, really, really want to shift the needle, [with] $2.4 trillion not a lot of that has to move in order to, again, create huge difference in terms of what’s possible for us here.”

Do you know more? Contact James Riley via Email.