Earlier this year, Industry and Science minister Ed Husic stated that he wants Australia to have a high-performing innovation ecosystem where universities, research institutes, government agencies and big corporations collaborate.

This is an ecosystem, he says, where great ideas can be pressure tested and put in place; technical challenges overcome; investors brought on board; and startups progressed.

Australian researchers are some of the best in the world. Less acknowledged, are the quiet achievers who work with them in our universities and research organisations to get ideas out of the laboratory and into use.

These are the Technology Transfer Professionals (TTPs) committed to a collaborative, creative endeavour that translates knowledge and research into impact on society and the economy.

Despite their critical role in commercialising research, TTPs remain overlooked, undervalued, and underfunded in the innovation ecosystem. The lack of investment in – and support for – TTPs has long created a bottleneck that is slowing and missing commercialisation opportunities, to the country’s social and economic detriment. To remedy this, we need to ensure all elements of the ecosystem are adequately funded and supported.

The challenges facing TTPs are not new – and are not restricted to Australia. In 2016, a major UK report on technology transfer by the McMillan Group noted the myriad of tensions between university governing bodies; university senior management; academics; early career students, and investors/corporations because of their different perspectives, aspirations, and expectations.

The report said it was typically the role of the TTPs to manage all the tensions. “They need to both support academic and student entrepreneurs, and also act as the face of the university – rationing resources, turning down academics/students eager to commercialise ideas they believe in, and managing risks,” the report said.

TTPs need to make “careful judgements on which exploitation routes are most likely to deliver impact, and to negotiate with academics, investors and funders, and advise senior management accordingly”.

Given that it is impossible to always keep everybody happy, the report lamented “the odds are stacked against technology transfer staff being popular”.

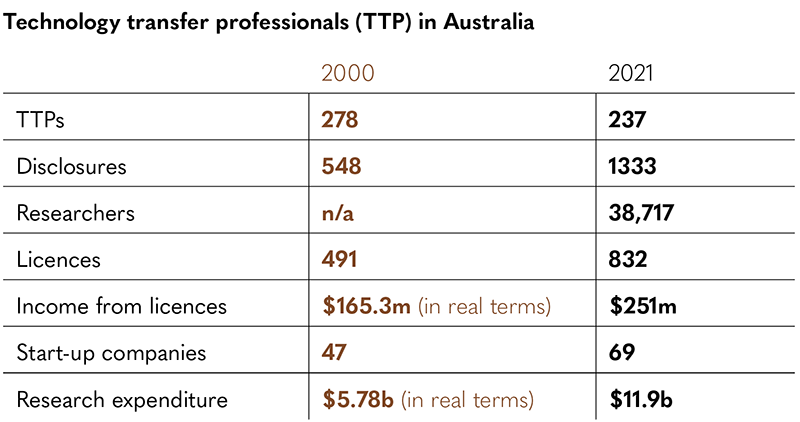

When I started in commercialisation more than 20 years ago there were 278 technology transfer staff in Australia. TTPs are responsible for identifying, documenting, evaluating, protecting, marketing, licensing and spinning out the organisation’s intellectual property.

Surprisingly in 2021, there were 237 (15 per cent less) TTPs in Australia. Let that sink in for a while…

Not only were there 15 per cent less tech transfer staff but those staff recorded 1,333 researcher invention disclosures (up 143 per cent), completed 832 licencing deals (up 69 per cent), earned $251m in revenue (up 52 per cent) and spun off 69 companies (up 46 per cent). And while TTP numbers have shrunk, research expenditure has more than doubled from $5.78 billion (in real terms) in 2000 to $11.9 billion in 2021. You don’t need to be a mathematician to determine that TTPs are under workload stress.

The obvious question here is why hasn’t the number of TTPs grown to reflect the increased need for their skills and expertise? As many bemoan, TTPs are seen as an expensive ‘cost centre’ where expenditure needs to be contained, restrained, and reduced.

This is a short-sighted view as there is an opportunity cost of Australian innovation and ideas not getting to market efficiently. If our competitors get there before us this can be measured in terms of fewer new skilled jobs and less Australian exports.

Traditionally (until COVID-19) revenue from research grants and international students was a stable and increasing income for universities. With the government redirection of funding (through the 2009 Backing Australia’s Ability strategy) to encourage research organisations to focus on engaging with industry, contract research has now grown to $800m in 2021. While the revenue is valuable and helps the industry, the big innovation is not where it occurs.

More business development and industry engagement people have been employed at universities for driving this growth. However, to maximise the full value of having these additional customer-focussed people it’s important that they work closely with TTPs, as their customer bases may – and should – overlap with deeper engagement possible.

Many Australian universities are starting to shift from a purely linear technology push of researcher-created technology looking for a problem to apply it to. By integrating – co-locating industry engagement and TTPs – they create a technology pull with industry-ready solutions.

Deep technologies typically take 10+ years of concerted and continuous effort to move from development to commercial reality. However, with offices of TTPs turning over on average every three to five years, this effort is compromised. Building and maintaining relationships with researchers and industry partners becomes difficult, and corporate knowledge is lost. Continuity of effort is disrupted, leading to missed commercialisation opportunities.

Under-resourcing and difficulties acquiring skilled talent means large and small tech transfer teams are battling to keep up with demand, let alone educate researchers to become more industry and commercialisation savvy. This lack of resources means limited services are offered and many opportunities are missed.

This cost-centre mentality approach, instead of seeing a long-term opportunity, is costing Australia. When Australia spends $1 on R&D it reaps $5 back in economic development. In 2021, the R&D investment of $11.9b would equate to $59.5b being added to the economy. But this return multiple could be much higher if not for the tech transfer bottleneck.

TTPs have evolved over the last 20 years with more women across all levels. However, despite greater flexibility in working arrangements, the sector also experienced the ‘great resignation’ after COVID with job vacancies more than doubling.

Our July 2023 desktop research using research organisation staff web pages and LinkedIn profiles paints a picture of what TTPs look like today.

Two hundred and thirty-five TTPs were identified (not including IP staff and operational and administrative staff) from 56 institutions (including 30 universities, 20 medical research institutes and 6 research agencies).

In 2016 Knowledge Commercialisation Australasia (KCA) and gemaker developed the world’s first capability framework (that has been used internationally) to identify the competencies required by TTPs to successfully commercialise research out of Australia’s public research agencies. The areas TTPs and their external stakeholders nominated as needing the most development were business acumen, strategy, marketing, social media, relationship building, and communication.

Whilst 50 per cent of current university-based TTPs have a PhD and 60 per cent of medical research institute TTPs have a PhD, it is not a requirement for the role. What is essential is empathy for researchers. People with undergraduate degrees and broad business knowledge can equally plug the gaps.

Traditionally, the larger universities have been the main training ground for TTPs as they have a larger critical mass. Some of them, like Monash University, have had teams in place for over 10 years.

However, the growth in venture capital firms, startup companies, trailblazer universities and incubators/accelerators has been sucking experienced TTPs out of the universities faster than they can train them. We need a deeper pool of talent to draw upon.

The following suggestions are aimed at developing a roadmap to address our innovation ecosystem’s short and long-term strategic needs.

In the short term, we need to step up technology commercialisation capability.

Targeted funding support is needed to create more tech transfer positions to train and service the growing demand for translation services.

Successful tech transfer requires core staff to be located at the institution to facilitate the identification of opportunities and early commercialisation or protection. Additional funding for smaller regional and large universities and other research organisations, would allow the core staff to access a national panel of technical and commercial specialists to broaden their expertise and networks as needed.

There should be dedicated funding for developing commercialisation capability within smaller regional and large universities and other research organisations, including training researchers and upskilling existing TTPs.

KCA and Cooperative Research Australia members, through their individual successes, provide clear evidence that sustained government efforts to build and extend commercialisation and translation capabilities deliver impressive outcomes.

I believe a new government-backed, scalable commercialisation and translation capability program would drive commercialisation skills initiatives, growing Australia’s long-term skills and capability policy framework.

A lot could be learnt from the recent US investment of US$50b in innovation, which incorporates US$3.1b to support the increase or establishment of technology transfer capacity across the country.

Under our proposed program participants would learn how to combine their technical and specialist skills with the business-building and negotiation skills required to create new markets and industries. They would also work with government on how policy is developed. The program would create new understandings of how different parts of the innovation ecosystem operate – and need to cooperate – and how networks are built to develop emerging industries.

Longer term, we need an education system that drives innovation.

Australia needs a more skilled, creative, and adaptable workforce to become a robust productivity powerhouse. Training in STEM innovation and commercialisation must become core in primary, secondary, tertiary, and vocational education – i.e., at every stage along the pipeline for future researchers and industry workers – to drive long-term productivity gains.

There needs to be long-term government support to:

- Introduce students – regularly, from early primary school onwards – to innovative STEM role models in diverse (technical and commercial) rewarding careers and innovation examples linked to their subject materials.

- Increase innovation training in undergraduate STEM courses and provide commercialisation capstone subjects at the end of degrees

- Encourage the uptake of double degrees – technical with business-related degrees.

- Create specialised PhD and post-graduate training including micro-credentials courses to build capacity for translating research outcomes (e.g., product development and manufacture) into commercial success; and

- Fund and support direct research-industry engagement and commercialisation training to help industry and researchers identify clear pathways for innovation translation.

- Of course, universities are already doing things in this space.

Monash University has found its Industry PhD program and double degrees with STEM and business popular with students and employers. Their Monash Innovation Guarantee is an intensive unit where students work with industry on solving real problems.

QUT hosts interns for work-integrated learning from the business school and plans to have commercialisation internships for PhD students. Their QUT Entrepreneurship Inside Innovation initiative includes site tours to innovative start-ups, hubs, and businesses.

UNSW’s Chemistry of Cosmetics and Personal Care Products course is a great example of appealing to a wider range of students by incorporating innovation and commercialisation principles into a technical subject.

Students are taught about the interaction of skincare chemicals with the skin’s natural fats and how sunscreens filter or scatter UV light. They also learn how cosmetics are manufactured and how they are marketed to particular consumers (e.g. anti-ageing solutions). The great thing is that innovation and commercialisation are seamlessly taught with science.

Australia consistently ranks well against its OECD and international counterparts in creating new research and exciting ideas. However, we consistently rank below average on translating new ideas into business. Australia is also good at investing in infrastructure but not as good at investing in its human capital.

The solution lies not in trying to turn researchers into entrepreneurs, or just telling them they need to engage with industry. Broader cultural change is required. We need to focus on not just having a STEM-literate society but also innovation and business-literate society too.

If we want to realise our full potential this must involve dealing with the serious shortage of people skilled at working in that vital space where academia and industry meet.

We must create a long-term national strategy to cultivate the next generation of tech transfer professionals if we aspire to be a top-tier innovation nation.

Natalie Chapman is a STEM commercialisation and marketing expert, with more than 17 years’ experience turning innovative ideas and technologies into thriving businesses. She has directed the strategic commercialisation of multiple innovations in mining, energy, environment, advanced materials, medicine and defence and has helped launch successful research spinouts. In 2011 she founded commercialisation consultancy gemaker and continues to advise universities and companies on innovation.

Warren Bradey is an experienced commercialisation expert, senior executive and company director who has started, led and grown many successful Australian-based, global businesses.

Do you know more? Contact James Riley via Email.