Last week was OECD week; but in Australia about the only coverage was the OECD concern about our housing prices.

Despite Australia being the 23rd member of the OECD (joining in 1970) the organisation doesn’t get a lot of press in Australia. It should get more.

The two-day OECD Forum last week that formed the core of the week and led into the OECD Ministerial was organised around the theme of Productivity and Inclusive Growth. Sounds familiar, doesn’t it?

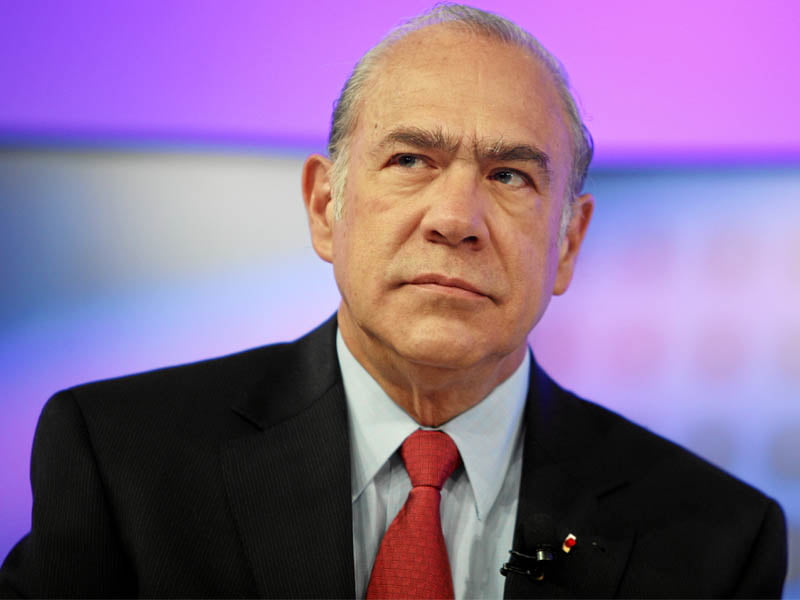

Angel Gurria, the OECD Secretary-General who is starting his third five-year term, opened by reminding us that eight years after ‘the crisis’ (the GFC), growth is sluggish. In terms of productivity the crisis only marked the point at which a bad story has become worse.

Global productivity growth was strong in the 1990s. It slowed at the turn of the century, but has been half that already slower rate since the crisis. The boom in Australia in the 90s was attributed to the twin effects of structural reform and of the increased use of ICT.

The relevance of each, and even the extent of the growth, is contended. (For example John Quiggin has always argued the statistics underestimated the impact of the increase in hours worked per employee).

Identifying which structural reforms had the greatest impact is also contended. Some would argue it was a ‘smaller government’ effect from deregulation and competition policy. It is also argued that it was the consequence of the ‘Accord’ which was a highly interventionist role by government that increased the social wage in a trade that allowed greater flexibility to be delivered in workplaces.

As InnovationAus.com has previously noted productivity is merely output divided by inputs, and really is hard to work on directly. It gets confused, even by the OECD, with firm level efficiency; as a consequence they agonise over the fact that some sectors are even becoming less productive.

Firm level efficiency really only covers what economists would call productive efficiency (doing things right) but not allocative efficiency (doing the right things).

But the forum wasn’t only concerned with productivity, but also ‘inclusive’ growth. The OECD released a new report The Productivity-Inclusiveness Nexus which makes the case against ‘trickle-down’ economics. The release accompanying the report notes:

The Nexus report also shows that inequalities of income, wealth, well-being and opportunities have increased in a majority of countries. It highlights how different aspects of inequality tend to feed off of each other, hindering efforts to improve individual well-being and undercutting our economies’ productive potential. It notes in particular how low income groups and regions that have fallen behind tend to accumulate economic and social disadvantages.

Higher inequality results in fewer people in the bottom 40 per cent of the population investing in skills, thereby worsening inequality and reducing productivity growth. The report says increasing productivity dispersion across firms appears to have contributed to a widening of the wage distribution over the past two or three decades.

The report highlights how the growth of the digital economy raises new challenges for jobs and skills. It adds that the growing weight of finance in the global economy may have diverted investment away from productive activities, while resulting in a higher concentration of wealth at the top of the income distribution.

This raises three important issues; that inequality itself is a source of declining productivity, that digitalisation raises new opportunities and challenges, and that the growing weight of finance may have diverted investment from productive activities.

In the OECD’s Economic Outlook also released at the forum also noted that monetary policy cannot pull the world out of its sustained economic slump and called for coordinated fiscal policies and structural reform (of service industries).

It is interesting to note that even if the Liberals assertion that the FTTP NBN was going to cost more than FTTN, the OECD prescription is the former was a better economic policy – a productive use of fiscal policy that turned investment today into an income stream in the future.

But it is the implication of the productivity report for Australia’s innovation policy that raises the most important questions. In particular digitalisation is important, but it is most important where it is creating new products and services, not just “disrupting” existing services.

Secondly innovation policy that focuses on ‘startups’ is at risk of compounding the inequality problem. Arguments about the need for lower tax or better migration laws to import ‘talent’ run counter to the need to reskill the entire population.

Finally the OECD is also recognising the distorting effects of the finance industry that has led to what Time magazine has referred to as American Capitalism’s Great Crisis. Stated otherwise ‘financialisation’ (the increasing importance of finance, financial markets, and financial institutions to the workings of the economy) is having its own effects, which have been noted by Gerald Davis and Suntae Kim as including shaping ‘patterns of inequality, culture, and social change in the broader society.’

A fixation of equating innovation with ‘startups’ plays into all these biases. Discussion focuses on the stages of investment and new economic roles of angels, venture capitalists, incubators and accelerators. The goal seems to be more about making a few people rich as it does growing the economy as a whole.

The OECD Forum was not immune from modern trends, however. I joined a Discussion Café on the theme Silicon Valley Everywhere? At a table with the Marianne Vikkula the President of Slush, Valerie Mockler, Principal Researcher at Nesta and Michael Nelson from Georgetown University we discussed all the standard ideas. After reviewing all the observations of everyone else (using software from be-novative) we came to a very simple conclusion.

Policy makers need to be a bit like innovators themselves, stop analysing and just do. Support what works, rather than trying to recreate another model.

But if I go back to the wider OECD theme there is another prescription. Make sure you are backing the innovations that grow the economy, not those that just add to the problems of the global economy.

Do you know more? Contact James Riley via Email.