OPINION: In late 2018, the collective of energy ministers tasked the Energy Security Board (ESB) with developing advice on a long-term, fit-for-purpose market framework to support reliability that could apply from the mid-2020s. This became known as the post 2025 market design project.

After close to three years of work, the ESB has delivered its final report.

As everyone knows, we are in the midst of a transition in our electricity system. The need to reduce carbon emissions is the motivation for the transition. However, the consequence is a move to more small generating facilities that are dependent on weather (solar and wind), more storage options (batteries and pumped hydro) and distributed resources (rooftop photovoltaic [PV], home batteries, vehicle-to-grid electric vehicles [EVs], and controllable loads like pool pumps and hot water).

The most contentious part of the report is a recommendation to introduce a capacity mechanism to address resource adequacy, whether there is sufficient generation capacity to service demand. The ESB noted in their overview of submissions received on their options paper, “Most considered there is not a material resource adequacy problem in the national electricity market (NEM) and broadly supported the continuation of current market regulations and arrangements.”

The parties who considered resource adequacy problems were emerging were generators who owned coal plants.

Despite this lack of support, the ESB has proposed a capacity mechanism, but hasn’t offered a design for one. A capacity mechanism generally requires that “dispatchable” resources are contracted to be available and paid even if they are not called on to provide any electricity. The biggest concern is that it distorts the market and keeps coal (and gas) plants in the market longer, and suppresses more renewables and storage.

In a 26 August opinion piece for the Herald-Sun, Energy and Environment Minister Angus Taylor backed the capacity mechanism. He argued Australia faces risk from current investments trends, saying:

We had a glimpse of what such a future would look like following the sudden closure of the Hazelwood power station in 2017, when electricity prices skyrocketed by up to 85 per cent in Victoria, 63 per cent in NSW and 53 per cent in QLD.

Families should not have to choose between using their heater and cutting back on everyday essential items to pay their electricity bills. Nor should they be asked to ration their use of electricity to prevent overloading the grid and causing blackouts.

There are real problems with this description.

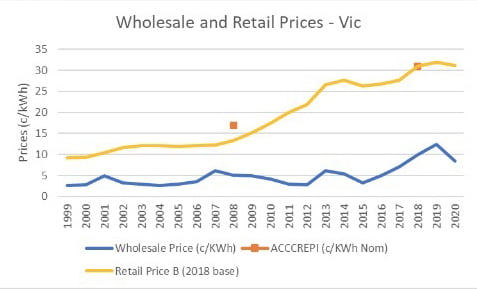

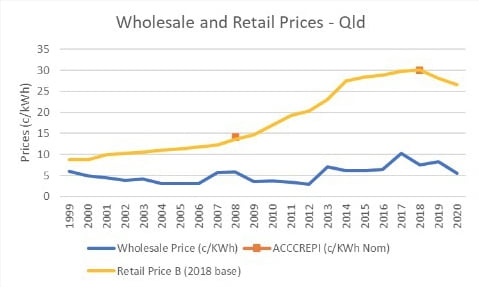

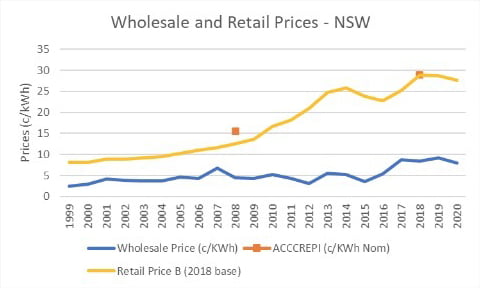

The minister has used a classic misdirection to heighten a sense of crisis by confusing wholesale electricity prices with consumers’ prices. The three diagrams below show the wholesale and average retail consumer prices for electricity in the three states. The price increases the minister used were wholesale; retail consumer prices were much lower. Further, the wholesale prices have already declined from those peaks.

(Retail and wholesale price comparisons. Source: AEMO aggregated price and demand data, ABS CPI electricity index, ACCC REPI price calculations)

The minister is right that households shouldn’t have to choose between using electricity and other essentials of life. But whether they need to choose between heating and eating is an income question, not a cost question. But the idea that consumers might respond to high prices at times of short supply was a reason for moving to the market arrangements. It is called demand response (or demand-side participation) and remains a core policy objective.

But the most damning evidence on a capacity mechanism is the Australian Energy Market Operator’s (AEMO) annual electricity statement of opportunities (ESOO). In their summary of the ESOO, called AEMO’s Reliability Outlook 2021, AEMO notes, “No reliability gaps are forecast for the next five years.” AEMO also notes the increasing unreliability of coal generation and that rooftop solar is transforming the grid.

AEMO also notes that demand could increase very quickly if the electrification of other sectors accelerates. One of these sectors is transport, which has two-fold impacts if electric cars have vehicle-to-grid capability. People who work in campus locations with expansive rooftops could be getting their electricity from their employer courtesy of the ability to charge their car at work during the day, then driving it home to power the house.

So a great increase in demand could be accompanied by an even greater shift to decentralised resources. It remains surprising that what the ESB calls integration of distributed energy resources and demand side participation is the third of the four issues they address. It isn’t surprising that they continue to think of this as “integration”, making DER fit the market. What is really required is facilitation, making the market fit DER.

The short answer to the question of “will the power go out?” is “No”. But the work of the ESB and energy ministers isn’t contributing to securing that outcome.

Do you know more? Contact James Riley via Email.

It’s possible there might also be a few electrical engineers (and large industrial consumers) who think that a mechanism to ensure ongoing supply (and grid stability) is worth locking in.

This article reminds me of the joke about the academics stranded on a desert island with nothing for sustenance but some canned food.

“How are we going to open these cans? “asks the historian.

“Let’s assume a can-opener?” says the economist.

Despite AEMO’s public optimistic utterances, we are still far from certain how we are technically going to manage supply and stability needs with increasing volumes of renewables in the grid – especially largely uncontrollable roof top solar.

Best case is we will probably muddle through, but probably after paying way more than we should for systems and technologies that might prove redundant as we scramble to cope with an ever-increasing volume of renewables.

“Did someone say SMRs?”