The Productivity Commission was a creation of John Howard and Peter Costello. They brought together the former Industries Commission with two other economic advisory agencies: the Bureau of Industry Economics and the Economic Planning Advisory Commission.

The Industries Commission, in turn, was the product of an earlier merger of the Industries Assistance Commission with the Interstate Commission and the Business Regulation Review Unit.

It doesn’t take a genius to realise that the concentration of economic advice to the government can result in one of two outcomes: either a high-performing, super-charged policy powerhouse or a less vibrant policy culture.

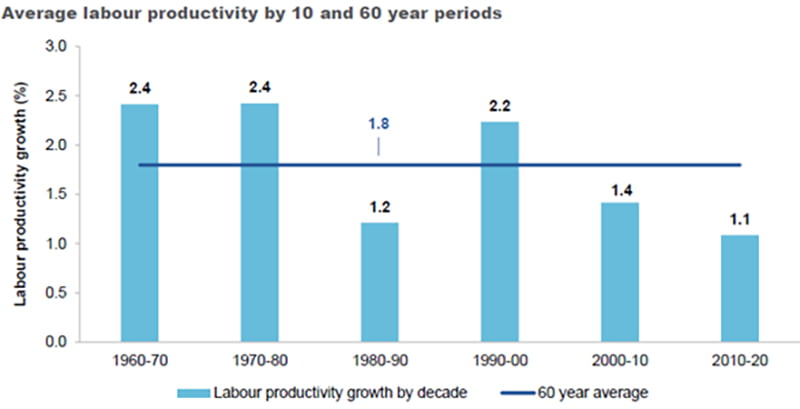

If we measure the Productivity Commission based on its avowed mission – improved productivity – it has, in its most recent five-year Productivity Inquiry: Advancing Prosperity, commenced with accepting its abject failure. The PC reveals this in the first figure in the report, which they labelled Labour productivity growth is at its slowest in 60 years.

There has been a steady decline in labour productivity growth since the middle of the decade in which the Howard Government created the PC. A former PC chair responded to an earlier version of this data that the PC wasn’t responsible for that; government just didn’t implement their recommendations.

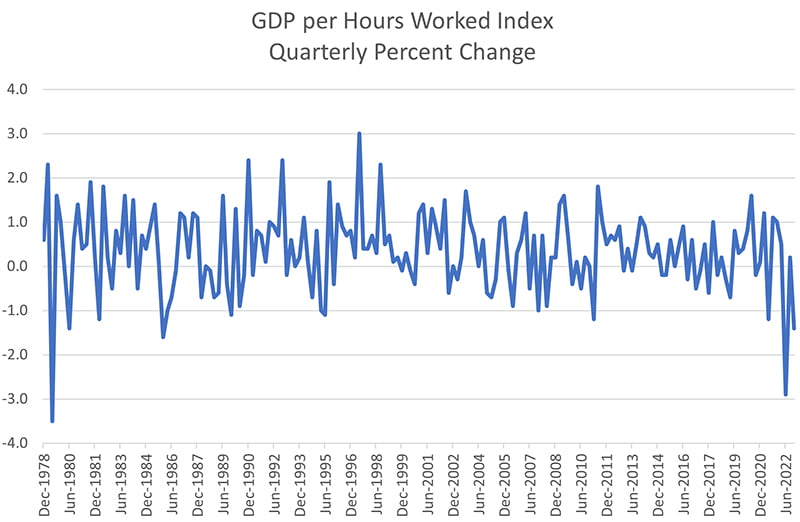

But the cause of this decline is more deep-seated than that. Firstly, it began simply with the language change from an industry development focus to a detached economic analysis. Secondly, it is because the productivity measure of the change in GDP per hours worked is stupid, because the hours worked wanders all over the place, as shown below.

This is a very crude measure, and fails to account for the simple fact that each unit of labour is not equally productive. To put it very simply, if the productivity of labour fell into two groups, one with higher productivity than the other, then the simple measure of productivity would increase if all the labour of the less productive group was not performed and its associated output not achieved.

In his defence of the report, Commissioner Stephen King has noted services now account for 90 per cent of our workers and account for 80 per cent of our economy. He asserts that they are hard to make more productive.

The good news for innovators is the hope he sees in the use of digital technologies in sectors like education and health. This begs the question of how to get a consistent digital economy strategy, given the twists and turns that date back at least to Richard Alston’s National Office for the Information Economy (NOIE).

In a 2002 paper titled The National Office for the Information Economy: promoting government service delivery using new technologies, the General Manager of NOIE’s Government Services group observed:

“Egovernment, or the transformation of government service delivery through the appropriate use of new technologies has the potential to improve the lives of Australians by delivering better Government and better services to citizens and businesses.”

This quote masks one of the risks in production statistics that they may under-value quality improvement. However, twenty years after that paper was written the most notable application of digital technologies in government has been the Robodebt.

Professor King argues that in the services sector we spend too much time looking at inputs rather than outcomes. However, the PC report itself is almost entirely focused on inputs. This is a natural thing for an economist to do, being trained in a discipline that treats a production function that converts inputs to outputs as almost the definition of an industry.

One way to focus on outputs is to look beyond the least productive 90 per cent of workers and instead ask how we can increase further the output of our most productive workers. This is where the whole concept of developing “value-adding” industries to the agricultural and mining sectors that underpin our economic growth.

That there was nothing about manufacturing, given its importance to the current government, perhaps explains the interest of Treasurer Jim Chalmers in “ways to broaden and deepen [the PC’s] focus on prosperity and progress more broadly” to maintain the Productivity Commission “as a powerful and prominent source of independent advice to government.”

The Treasurer has “been having conversations with various experts over the course of the last couple of months about how we go about that, I think it’s an important thing for us to consider this year.”

Responses to this vary. The Australia Institute welcomed the review while being scathing of the PC’s performance. The Australian Manufacturing Forum (which is a LinkedIn group) suggested the Government just “ditch this industrial dinosaur”, a call supported by the ACTU. Unsurprisingly the AFR found commentators prepared to label the abolition proposal as “madness”.

Australia’s key institutions like the PC and the CSIRO are habitually ignoring the prospect of industry policy. While the Hawke-Keating reforms were famous for their focus on microeconomic reform and competition, they did not ignore industry policy. That disease descended in the Howard era and has endured.

Like the CSIRO, the PC is beyond redemption in this regard. It is clear that the concentration of economic advice in the PC has resulted in a less vibrant policy culture and not a policy powerhouse. The PC needs to be abolished and replaced with at least two separate bodies.

The first is something that looks like a merger of the old BIE with the Industries Commission with a mandate to advise on how Government policy can best support growth in industry (including food processing, mineral refining and manufacturing). The second needs to be focused on a narrower set of economic issues that seeks to understand overall the relationship between Australia’s resources (natural, human and entrepreneurial) and its outputs. Both need to be afforded the independence that comes from being established by legislation.

A third possible organisation is, in combination with a revived NICTA, something that drifts towards NOIE with a remit over the Digital Economy. Unlike both NICTA and NOIE, this third body should also be afforded independence by legislation.

David Havyatt is a former telco executive, former adviser to Federal Labor ministers and former advocate on behalf of energy consumers. He is a long term observer of Australian innovation policy.

Do you know more? Contact James Riley via Email.