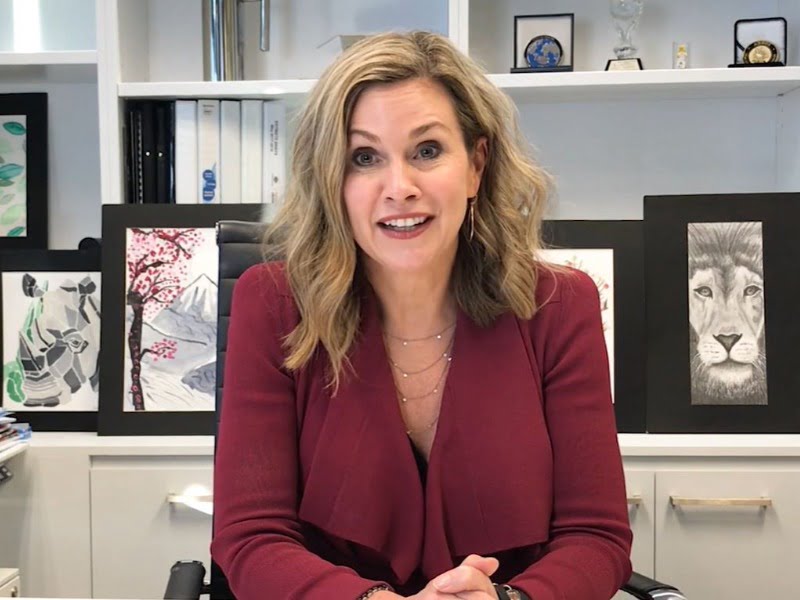

Australia’s eSafety Commissioner Julie Inman Grant hopes to take the public along with her as her office explores how to implement a scheme that would prevent anyone aged under 18 from accessing online pornography.

It comes as Ms Inman Grant acknowledged that using the federal government’s own digital identity system for verifying people’s ages, as agreed in-principle by the government, would be unpopular.

Recommended by a bipartisan parliamentary committee in February last year, the eSafety Commissioner is now leading the development of an “implementation roadmap” for the so-called age verification regime after the Coalition government announced in June that it would be tasking her office with researching it, consulting with industry and reporting back.

Also in June, the Coalition government agreed in principle to using the government’s digital identity scheme to verify the ages of people accessing pornography, but said a roadmap will be developed to determine whether this is actually necessary – and this could take up to 18 months.

Ms Inman Grant’s office began consultation with industry in mid-August and is not expected to report back to government until next year, when an election is likely.

If it’s recommended the scheme goes ahead, it is bound to be controversial. In the UK, a similar scheme was dumped following technical troubles and concerns from privacy advocates.

Speaking to InnovationAus in an interview last week, Ms Inman Grant said she was exploring different systems for age verification.

“I think the vast majority of Australian adults probably, you know, wouldn’t want to use a government-owned digital identity system [to access online pornography],” she said. “But there are tonnes of verification vendors out there — literally hundreds — that are kind of emerging that are offering different systems.”

While the UK scheme failed, Ms Inman Grant said she was “trying to actually bring the public along” with her for the Australian proposal to work.

“I don’t think they brought the public along,” she said of the UK’s attempt.

“There were too many concerns about the proposed methods that they were using; they weren’t secure and they weren’t private and they were using Pornhub and credit cards [for age verification].

“I think in the end, the government pulled it right before the last election. So maybe there was a political dimension to it. … There was a lot of very hot debate there. We’re going to try and learn from that experience.”

If UK citizens didn’t have a credit card, there was also a proposal to allow people to buy a “porn pass” age verification document from a newsagent.

The scheme failed in the UK because of “a couple reasons”, Ms Inman Grant said. One was that they were intending to use credit cards as tokens, “and they weren’t designed that way”.

Another was because the UK was “entrusting Pornhub to run the age verification system, and who’s going to trust Pornhub to have all that private data?”

“If you don’t balance the privacy, the security and the safety imperatives, it’s not going to work,” she said. “If you’re creating a honeypot of really sensitive information, it’s not going to work.”

As part of her research into making the Australian scheme work, she said her office was looking at how technology has evolved, including by looking at blockchain, biometrics and facial recognition.

“There are age-verification solutions that are out there that use biometrics and facial recognition,” she said. “We’re not saying [we will] go there at all. We’re assessing the technologies that are out there, the tools that are out there and what we think the policy and the regulatory leavers and groundwork needs to be.”

In addition to consulting via submissions, Ms Inman Grant’s office will also conduct roundtables, including with the sex industry, and speak with “a lot of vendors who will want to sell their wares”, she said.

Following this, a recommendation will be made to government, she said.

“The government could either say, ‘yes we take that and we think that’s a good idea, we’re going to legislate around those lines’ or they can say ‘we’ll note it’, or they could say ‘no we’re not going to accept this’ for one reason or another.

“So we have about 12 months to do this work. Some people think that’s too long. I think it’s going to be tight. My focus is on getting it right.”

Do you know more? Contact James Riley via Email.

Good luck with this endeavour my first impression is that there is a healthy suspicion of the Government generally and when we see other systems “creeping” into new territory it is hard to imagine how you could bring the public along with this. Historically the Government have not been able to resolve some really basic and non-contentious items that you can get unanimous agreement on “no child in poverty”, “housing affordability” for example so what would make the government think that such an emotive issue could achieve buy in?

In my humble opinion the primary reason for this lack of credibility and trust in government is that we are far too short sighted and most decisions are open to negotiation around political imperatives that are on a very short timeframe.

This is an extreme overreach; government shouldn’t be regulating this sort of thing.

Why is it that those who claim to be defending safety are always inevitably pushing for authoritarianism?