There is absolutely no doubt that orthodox economic theory concludes that, where viable, competitive markets deliver the best outcome for consumers. What is less clear is whether the orthodox theory is reasonable.

Certainly, Australia’s major economic institutions subscribe to the orthodox theory. For example, in a speech to the National Press Club, the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission Chair Gina Cass-Gottlieb renewed calls first made by her predecessor in 2021 for substantial reform to Australia’s competition laws governing mergers and acquisitions.

Similarly, in its five-year Productivity Inquiry, the Productivity Commission included “address competitive market incentives in highly regulated sectors” as part of its prioritised reform directive of creating a more dynamic economy.

There are important caveats to the value of markets. These include understanding what factors (usually described as market failure) preclude markets from delivering this outcome and whether objectives other than short-term price are important to consumers.

The problem with the whole theory of market failure is that all markets fail to some degree. There are two cases, however, where it is generally accepted that the failure is so catastrophic that attempts to develop markets should be avoided.

These are natural monopolies (like all the networks that distribute physical substances to our homes – gas, electricity and water) and public goods (such as defence force or public street lighting). Formal definitions are included as notes at the end, but these describe extremes.

In her Press Club speech, the ACCC chair stated, “An example of the critical role that competition policy reform can play in economic transition is the 1995 National Competition Policy reforms that responded to the recommendations of the 1993 Hilmer Report.” This claim is often made but seldom verified.

Firstly, it ignores that Australia’s productivity slowdown followed the implementation of these reforms. Secondly, it ignores that reforms to telecommunications, aviation and electricity occurred before Hilmer’s report (for a discussion on electricity, see Chapter 1 of On the Grid ed G.Roger, for telecommunications and aviation, see Competition Policy in Telecommunications and Aviation ed S.G.Corones).

Government motivation for, and expectation of, competition reform in telecommunications is instructive. At the time, policymakers were highly influenced by Michael Porter’s third strategy book, The Competitive Advantage of Nations. Unfortunately, policymakers misapplied the theory to conclude that firms could not be successful in the global market unless they faced competition in the domestic market. (Porter’s theory was a more nuanced one of industry clustering).

This policy interpretation manifested in Gareth Evans’ May 1988 statement Australian telecommunications services: a new framework as:

“Against this background, the Government has developed policies which now seek to achieve the following newly articulated objectives…(5) to enable all elements of the Australian telecommunications industry (manufacturing, services, information provision) to participate effectively in the rapidly growing Australian and world telecommunications markets.”

The 1988 statement also established a review known as the Carrier Review or the Review of Ownership and Structural Arrangements (ROSA), which informed the 1991 reforms. Vanessa Fanning’s Behind the Telecommunications Act 1991: Policy Imperatives for Telecommunications Reform (in Corones’ book) shows that this belief continued through to the 1991 reforms.

Ms Fanning, the First Assistant Secretary of the Telecommunications Policy Division of the Department of Transport and Communications, notes, “The evidence indicated that liberalisation of the market was likely to stimulate expenditure on research and development by the dominant carrier…Telecom Australia had a lower expenditure on R&D than the dominant carrier in any overseas competitive market.”

More broadly, Fanning claimed:

“The telecommunications industry is generally considered to be one in which Australia has the potential to be a significant international player. The performance of the Australian carriers is already average or better than average in many areas and the country has the sophisticated skills, the technology and the capital to compete in the rapidly growing new markets in this region.

“The opportunities for participation in this market by Australian firms were expected to improve steadily, through technological change, innovation by service providers and increasing deregulation in both basic and enhanced services in international markets.

“Specific international opportunities were seen in five areas, namely, export of communications equipment (which had more than tripled in the previous eight years to $180 million); export of services, for example, providing network management services in overseas countries and the export of education and entertainment services from Australia; turnkey activity, an area in which Telecom Australia (International) and OTC International were already active; equity participation in overseas telecommunications companies, and network hubbing management.

“The Review concluded that the extent to which effective competition was introduced in the Australian market was likely to be the key determinant of movement in the costs, prices and service performance of Australian firms, both domestically and internationally, and hence in their competitiveness.

“The relative impact of the options on Australia’s ability to penetrate overseas markets would thus depend on the level of competition offered, how quickly it was established and how broadly it was focused.”

This is a long quote, but important to get a sense of how much the Australian government was committed to the idea that competition policy in telecommunications would pave the way to participation in overseas markets. The following section in the paper provides more detail on the expected prospects for manufacturing.

With the benefit of hindsight, one can acknowledge that the analysis presumed a continuation of the time division multiplexing model of telecommunications and that it completely missed the internet disruption.

But, equally, it wasn’t only Telstra that failed to grow internationally; almost nowhere did incumbent fixed-line carriers become successful entrants in other markets, with only some success with mobile offerings.

Most telling, however, is how rapidly the research and development activity declined, with each of the major equipment providers closing local R&D and, ultimately, the closure of the Telstra (formerly Telecom) Research Laboratory.

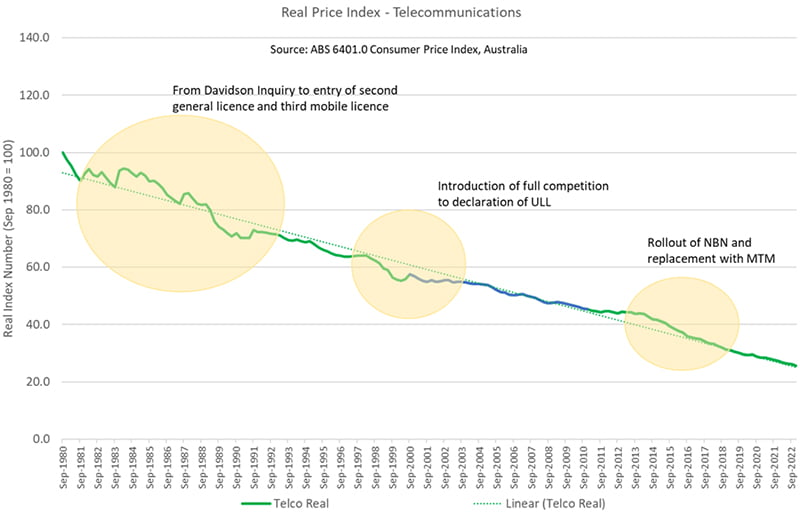

Even the claim that competition would reduce prices is debatable on the evidence of the telecommunications index of the CPI, which in real terms shows no sustained kink in the rate of decline aligned to the introduction of competition.

That is, the rate of decline has been driven by the rate of technology improvement and scale efficiency that has been in operation since the ABS first published this index in 1980.

Our economic institutions not only misrepresent the history of competition policy but also what our current and future expectations should be.

In the Press Club Speech, the ACCC Chair claimed, “New markets will emerge and develop in ways we can’t anticipate”.

She also noted, “A handful of large tech companies are playing increasingly important roles in our lives, as gatekeepers over how we interact with each other and businesses, and yet in many cases, these companies face only limited competitive constraint. Part of responding to these challenges is to encourage competitive, innovative and dynamic markets.”

The first of these claims is not strictly true, while the second is an example of how truly predictable this was. Responding to a paper on Institutional Requirements for Second Generation Reform at the ACCC’s 2002 regulatory conference, a discussant observed:

Consideration of these institutional arrangements for the regulation of monopolies, as opposed to regulatory agencies sometimes referred to as regulatory institutions, is going to become more important rather than less over future years. There are two reasons for this.

The first is that the nature of many of the industries of the information age represent a greater potential for economies of scale, be they demand or supply side economies, and the greater potential therefore for near natural monopolies to emerge.

The second consideration is the extent to which the ongoing information revolution is continuing to facilitate efficient organisation, and therefore reducing the transaction costs of organisation. This results in the boundary for declining returns to scale due to the internal organisational problems continuing to move out at a fairly rapid rate.

Despite the historic failures to deliver on its promise and despite the clear limitations of competition occurring in modern markets, our economic institutions continue to profess unrealistic faith in competition policy. The proposals for merger reform continue their desire to wish competition into existence.

Hopefully, Ministers will subject the calls for new ACCC merger powers to effective review and conclude that the solution is to accept the existence of market power and do more to regulate the market power. In brief, the ACCC needs to overcome its identity crisis and recognise that it can’t use “more competition” as the solution for all challenges and that sometimes it just has to regulate.

Technical Note

A natural monopoly exists when the cost function for producing the good is sub additive, that is, when all the possible quantities of the good can be produced more cheaply by one provider than by two or more. A good is described as a public good when it is nonexclusive and non-rival, which means that once the good is created, we can’t stop anyone from benefitting from it and that one person using the good doesn’t stop another person.

The question of natural monopoly is ultimately over what range of potential production economies of scale continue. Put simply, for things like car assembly plants, there is a point at which increased scale either increases costs or the amount of decreased cost is no longer larger than the cost of distribution over building another plant closer to part of the market.

A key source of economies of scale in the 21st century is “demand-side economies of scale”, which function exactly like network effects in that the value to each consumer increases as the number of consumers increases. This structure is typical of what the ACCC calls “digital platforms”.

Another class of goods (club goods) are non-rival but exclusive, yet in some cases, because the cost barrier for p[articipation is so low, they function almost as if they are public goods. Consequently, major economy-wide inputs (education, energy and communication services) border on public goods.

David Havyatt is a former telco executive, former adviser to Federal Labor ministers and former advocate on behalf of energy consumers. He is a long term observer of Australian innovation policy.

Do you know more? Contact James Riley via Email.