As custodians of our taxes, the Commonwealth government should be aiming to get the best return for the nation from expenditure on our public Universities. While the most recent decision by Minister Robert resulted in questions of ‘political interference’, the whole process is fundamentally flawed.

The release of the decision of the 2022 ARC Discovery Project has provoked outrage from university leaders and academics. The focus of the greatest outrage was the decision of the minister not to approve six applicants that the ARC had recommended.

The decision was decried for ‘political interference’, though the minister would argue he was doing his job in ensuring funds contribute to the ‘national interest’.

The announcement was delayed more than a month later than usual, presumably because of the minister’s scrutiny. All the approved projects suffered from this delay, especially those that require the hiring of additional staff or the award of PhD scholarships.

While it is easy to make these direct criticisms of the decision, it raises more fundamental questions of what our universities are for and how they should be funded.

A university is an institution of post-secondary education (aka higher education) that provides instruction by academics who are active researchers in the field. The research link is the primary distinction between Universities and Colleges, of which there used to be many before the sweeping reforms when John Dawkins was education minister.

In a Quadrant article Putting the Mass Universities Out of Their Misery, Peter Murphy identified three conceptions of the university: vocational, classical, and romantic (which he also calls socio-liberal evangelism). He argues that these developed sequentially.

The first stage was the establishment of the great universities to train priests, lawyers and doctors. Next, the expansion to the classical, focusing on classical literature, philosophy, mathematics, and later the sciences, also occurred through the great universities.

The final stage, the romantic or socio-liberal, has its origins in German universities mostly in the second half of the nineteenth century and was fully embraced in the USA. This development coincided with new social sciences disciplines and the expansion of the older political science and economics.

Conservatives struggle with the romantic university, as their support for the Ramsey Centre’ great books’ courses demonstrates. It is questionable whether all the courses taught at universities need to be taught by active researchers.

For example, professional teachers (rather than researchers) could teach law, accounting, nursing and teaching. These three conceptions of the university – vocational, classical and socio-liberal – can be seen as alternatives. However, they are more usefully viewed as a trio of objectives that a university seeks to fulfil.

The classical and the socio-liberal is a dichotomy related to the relative importance of a university disseminating the current state of knowledge and expanding the state of knowledge. The weakness for any university is to allow either one to dominate the other.

The motivation of the Dawkins reforms was to get more out of higher education without increasing outlays.

It had three core elements. First, reform was primarily meant to achieve scale efficiency by collapsing the two-tier system of 19 universities and 46 colleges into one ‘unified’ system of 36 public universities by various mergers.

The reforms also added to funds (at least notionally) by replacing free education with student fees supplemented by HECS. Finally, funds were diverted from block funding to competitive grants for research.

In another Quadrant article Moscow on the Molonglo, Max Corden criticises all the Dawkins reforms as a case of putting all of Higher Education under the direct, centralised control of the Commonwealth Government.

Corden argues that a motivation for the ‘sovietisation’ of the sector was that ‘Politicians and perhaps senior public servants showed a lack of trust in academics and, indeed, also in vice-chancellors.’

Corden’s critique had other targets than the role of the Commonwealth government in distributing research funding, but as an economist, he was very keen on the use of markets elsewhere. And here is the fallacy in the ARC model of ‘competitive grants.’

The decisions aren’t made by anything that looks remotely like consumers. It is just another (giant) committee of academics making recommendations about other academics, usually with little knowledge about the proposed research.

That there is then a political overlay with a minister proclaiming to act in the national interest is the very least of the concerns.

In New Knowledge, New Opportunities: A Discussion Paper on Higher Education Research and Research Training, David Kemp, as minister, estimated that, including those administered by the Australian Research Council and National Health and Medical Research Council, there were over 40 national competitive research granting programs relevant to universities.

The ARC alone administered nine programs. In Knowledge and Innovation: A policy statement on research and research training, the minister announced a restructuring of the ARC and simplifying two programs; Discovery and Linkage grants.

Competitive funding under a single grants body (well, two because there is also the MH&NRC) absent of any objective other than advancing research really is Moscow on the Molonglo.

The Discovery Grants are only one of twelve schemes the Australian Research Council administers. A competitive scheme would tie funding levels to outcomes from previous funding rounds (which is usually measured as research impact).

Universities would then internally allocate their funds to generate impact. (Research impact is a topic worthy of further debate on its own).

Not only is fund allocation made by a spurious competitive process, but the Universities are measured in part on their research income.

Overall, in the latest round, less than one in five applications were funded, and applicants received less than three-quarters of the requested amount. That is a lot of application effort for a small return.

But for some academics, the reward will come from their University for applying; they possibly don’t even need funding for their research given that 40 per cent of their time is already allocated to research.

This goes to the question of what research funding is used for. There are five main uses. The first is the obvious one of buying research equipment. The second, the equivalent in social sciences, is hiring survey resources or buying a dataset. The third is to travel to either use someone else’s equipment or access a primary source (read a document, see an artefact, interview individuals). The fourth is hiring a research associate or awarding a PhD scholarship. The fifth is buying out teaching obligations – that means giving the money to the university to hire casual teaching staff to change the individual’s 40:40:20 allocation.

Thirteen years ago, Jeffrey Goldsworthy from Law at Monash (Goldsworthy, J 2008, ‘Research grant mania’, Australian Universities’ Review, The, vol. 50, no. 2, pp. 17-24) labelled the process’ research grant mania.’ He summarised the position neatly:

Commonwealth funding formulae have caused Australian universities to become obsessed with maximising external research funding. Considerable pressure is applied to faculties, departments and scholars to apply for funding, and relative success in attracting it is given excessive weight in evaluating research performance. This may be productive in disciplines that require large amounts of research funding. But it can have many negative effects, especially in other disciplines, such as:

- a. it is a grossly inaccurate method of evaluating research performance

- b. the inundation of the ARC with excessive numbers of grant applications

- c. the diversion of funding from applicants who desperately need it to those who have much less need for it

- d. an enormous waste of time and effort on doomed grant applications that would have been better spent writing books and journal articles

- e. the giving of excessive weight to “grantsmanship” at the expense of substantive scholarship in determining appointments and applications for promotion

- f. subtle distorting effects on research agendas, as projects are devised in order to attract income rather than for their inherent interest and importance, and consequent damage to scholarly morale and enthusiasm; and

- g. the distortion of research agendas across entire disciplines.

Where there are actual government research priorities, research funding should be allocated using tender type processes designed around those priorities. This doesn’t mean short term contracts that look more like consulting, but big projects with bold ambitions.

Academics and universities should be expected to engage with the government to identify the big projects that should be funded. Otherwise, all government funding should be by way of block grants to universities.

Universities can be trusted to make these allocation decisions; what they regard as most important is their reputations which is measured in teaching and research outcomes.

The design of those blocks should have regard to how important it is for the subjects to be taught at a university with active researchers. It should also have regard to ‘research efficiency’, which should be measured by comparing a university’s research funding (from all sources) to its research impact.

Finally, it should also have a bias toward rewarding universities that attract funds from other sources, but this should only be contemplated as a means of allocating additional funds, not redistributing a limited pool.

Note: David Havyatt was a student Fellow of Senate at the University of Sydney in 1979 and a student member of the University Council of the University of Wollongong in 2020.

Additional notes:

In writing this column, the author tried to undertake some international comparisons. That effort revealed some inconsistencies in how Australian statistics are reported to the OECD, with any funds the universities generate from their own activity being classified as government. It also revealed that not-for-profit entities are where our university research funding is most underweight.

Underlying all this is a very imprecise formula that applies to funding. The funding for the university is based on the assumption that an academic’s time is divided 40:40:20 between research, learning and teaching, and governance and service.

Reforms by the Gillard Government haven’t helped. The extension of HECS to HECS-HELP, FEES-HELP, and VET FEES-HELP. This was accompanied by changing the enrolment model to be demand-driven rather than rationed.

The VET extension saw the vocational college re-entry to the structure. In keeping with the neo-liberal trend, the model encouraged the further development of private sector suppliers.

The most recent twist was the Morrison government’s misnamed Jobs-ready Graduates Package. This increased the student contribution per course. However, in developing this reform, the government has signalled a desire to move away from this model to funding teaching and research separately.

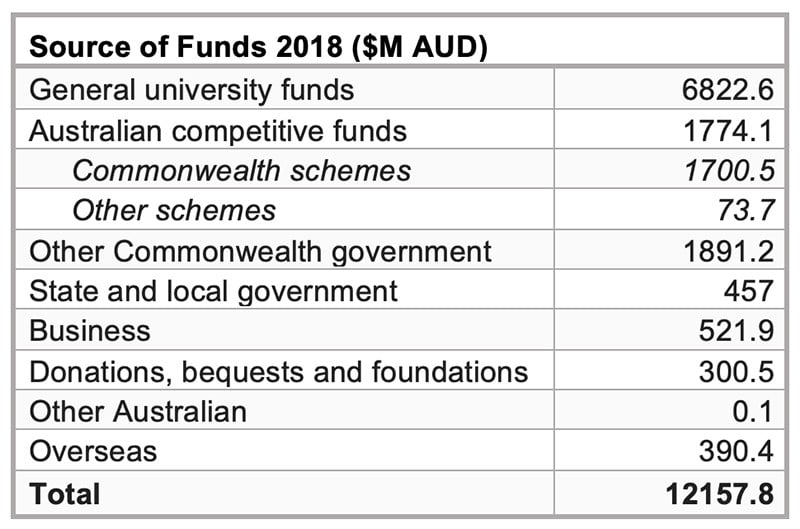

A Parliamentary Library Research Paper from January 2021 gives a good overview of total research funding for Universities. Extracted from this (which comes from the ABS) is this chart of the source of university research funds for 2018.

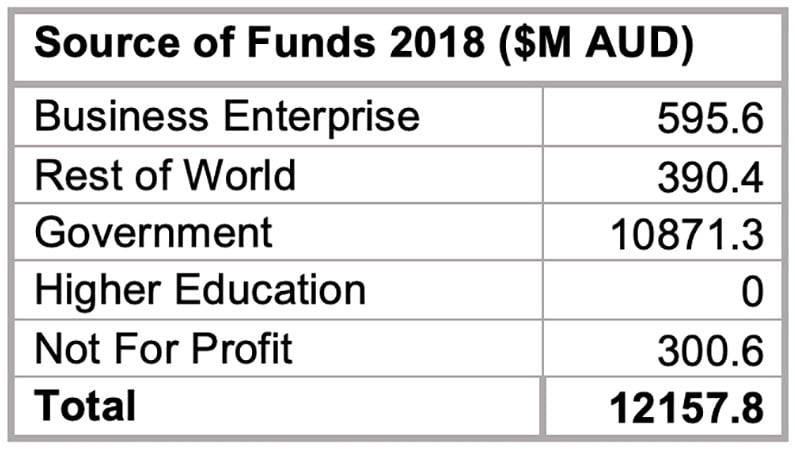

Unfortunately, it is tough to make international comparisons. The relevant OECD data set for 2018 provides the following data for Australia.

It is apparent from this that the Australian Government reports all funding from ‘General university funds’ as being from Government. However, much of this comes from fee income and university investments. Note that ‘other schemes’ under competitive funds are classified as Business Enterprise.

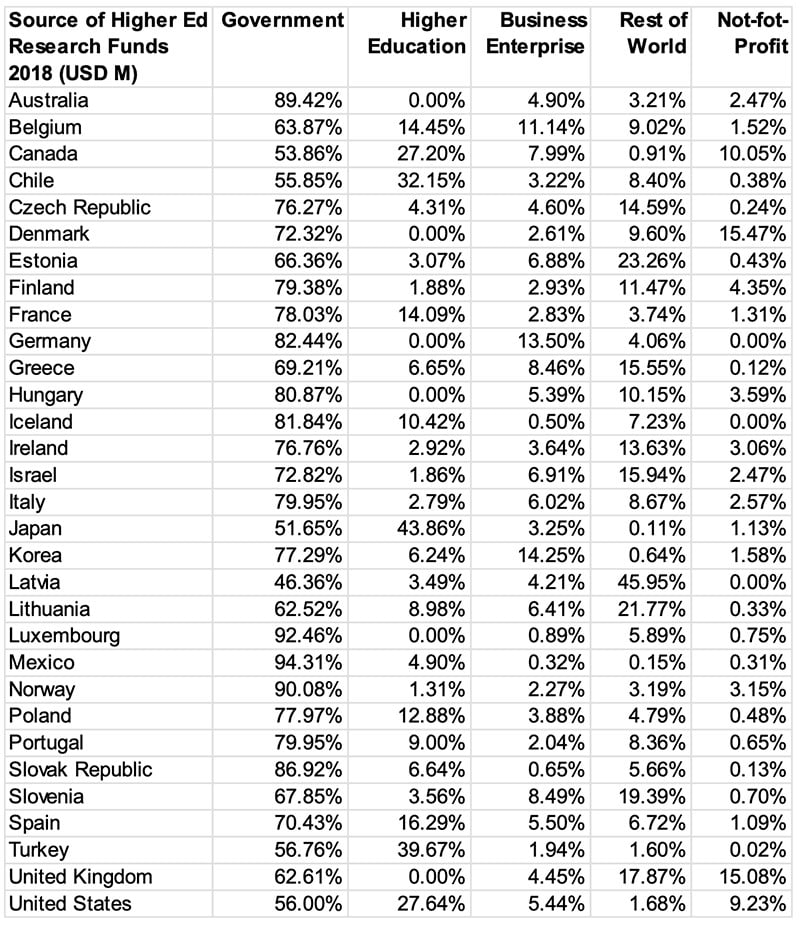

Noting this limitation, the chart below shows the OECD data (OECD Science, Technology and R&D Statistics Main Science and Technology Indicators, Volume 2021 Issue 1) for 2018 in millions of US dollars.

We can conclude that compared to the US and UK, we do very poorly on funding from NFPs.

Furthermore, the funding from the rest of the world is probably highly distorted by geography – a lot of that is likely to be within-Europe programs. Surprisingly, our level of funding from Business Enterprise is in the same range as the UK and US.

Finally, we are left with the big unknown of (a) how much of the funding in Australia (and the UK) should be categorised as Higher Education’s own funds and (b) how much of the government research funding is by competitive funds.

Do you know more? Contact James Riley via Email.

Excellent article. There is a better model, that solves for the recommendations well articulated in this article: national missions. They will require high risk and long term research agendas to succeed, but in the context of a larger outcome of national and/or societal, economic or environmental interest. The outcome of one research initiative, is the input to other/s in integrated programs. It will require more collaboration across institutions and disciplines. The model works. https://cdn.minderoo.org/content/uploads/2020/09/14223039/MFFFR-Blueprint-V1-200915.pdf

Adrian, thanks for that comment. I agree with the sentiment behind national missions, but I was terribly disappointed when the Govt innovation attempts decided on their first moonshot project. They went for genomic based health research and put hydrogen second. It works if you also recognise that you can have national missions around other things that are worth researching…ending the gap, eliminating poverty, telling Australian stories, constitutional renewal….