It’s odd to be writing something that aims to make its own subject – artificial intelligence (AI) regulation – redundant. But by the end of this decade, my hope is that we will have ceased to talk about ‘AI policy’ or ‘AI regulation’ altogether.

Not because the task of regulation will be complete. But because we will have given up on AI as a term of any use to bind together so many different software products, used in vastly different contexts.

By 2030, my hope is we will be on the way to a more precise vocabulary to describe the technical systems that concern us, and a more diffuse set of conversations about what is needed of these systems to make sure they are designed and deployed in ways that benefit us.

This is more than a hope, really. It’s an expectation. And an attempt to jog the conversation along.

History shows us successive waves of technological innovation, shifting from experimentation to rapid growth and ultimately to safer and more sustainable implementation. Each was made possible by the diffusion of expertise associated with that technology, and the emergence of new professions and new specialisations that reckon with its many forms.

If we are actually going to realise the promise of more robust, reliable and safe AI systems, then first we need to relinquish our desire to contain many different kinds of systems under the term AI in pursuit of making things simple.

New technologies necessitate new professions and processes

When electricity was first stuffed into a Leyden Jar in the 18th century, ready to be discharged at will, early experimenters glimpsed a future of endless possibilities.

In its first century, experiments with electricity gave rise to new sciences like electrotherapy, positioning electric currents as a panacea for a range of medical ailments.

People crowded into lecture halls to watch scientists attempt to reanimate the dead. Medical textbooks offered sage advice on how best to administer electric shocks to children.

Electricity was deployed as a cure for blindness, treatment for cancer, balm to an infected wound and tonic for any number of complaints soberly diagnosed as ‘women’s hysteria’.

Many of these treatments, first presented breathlessly and accepted uncritically, would ultimately be dismissed as quackery. Along the way, investors lost millions, patients were left out of pocket and people were injured, maimed and killed.

Some of these treatments, with the benefit of research and evaluation, testing, and safety standards, would go on to form part of modern medical treatment. They took on new names and shapes. In Australia, the possibilities of electricity for medicine would ultimately enable the invention of the electric pacemaker and bionic ear.

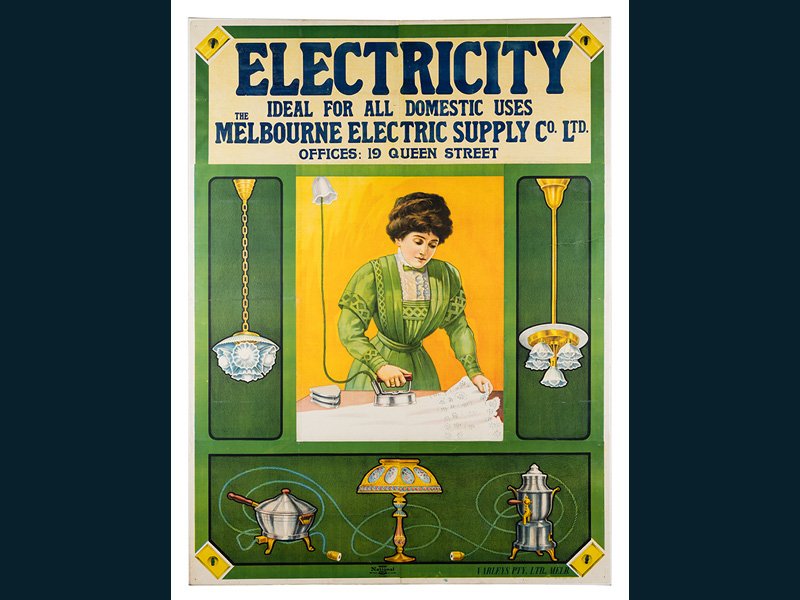

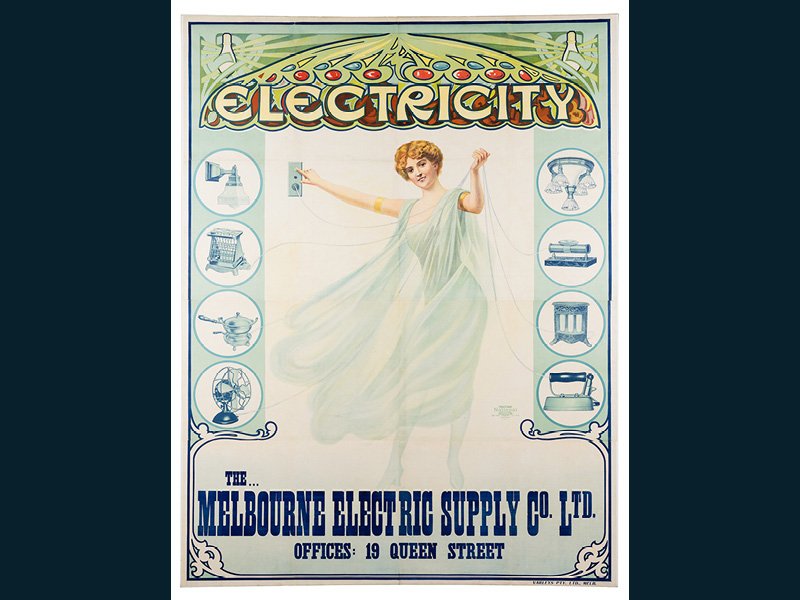

That first century also gave us the lightbulb, Tesla’s alternating current and induction motors, ushering in the Age of Electricity: the electrification of whole industries, public spaces, residential homes and appliances.

At the 1896 Chicago World Fair, millions of Americans crowded into noisy, whirring exhibition halls to marvel at early prototypes of neon lights and dishwashers. Switching on city streetlights was the ceremonial task of presidents and city mayors.

But these electrified things also caught fire, a lot. People were electrocuted. Early infrastructure was noisy, unsightly and quick to decay. As electricity became basic infrastructure supporting many kinds of trades and services, new professions were needed: licensed electricians, electrical engineers, line workers and power plant operators.

Early monopolies that dictated who got access to electricity grids and for how much were subdued by new forms of energy utility regulation. Energy markets were formalised, setting tariffs and cost structures around electricity distribution and use.

Wattages, plugs and sockets were standardised. New tools, processes and services were created for different industries, with safety, interoperability, robustness and repairability mandated by new rules and standards.

Today, more than 250 years after those first experiments with Leyden Jars, we wouldn’t even think to unify the many contexts where electricity has a role, or the professions that make them safe and sustainable.

Electricity is a form of infrastructure, an input for new devices and tools, and a service. An electrician wiring up a home looks vastly different from a bio-engineer prototyping electrotherapy devices, despite their shared enabling technology.

Instead, as electricity has infused every sector and society in Australia, we have evolved a system of skills and rules and expertise to deal with this diversity and nuance – just as we have done with other pervasive systems like the food we eat, or the transport that gets us and our goods around.

Each is now governed and shaped by a system that is distributed, complex and multilayered, and, as a result, more robust than any unified system could ever be. While it can still be tested, and severely (as we are currently experiencing), we have developed mechanisms to better monitor and anticipate impacts and levers for mitigation.

AI is often likened to electricity, for both its transformative potential and galvanising effect. And like electricity, AI is often invoked to describe a diverse set of actual tools or systems: inventions like search engines, chatbots, spam filters, robots, facial recognition, digital assistants, and recommendation algorithms – anything (as long as it’s new) that automates tasks using software.

Looking back over the long arc of history is useful, because software is so ubiquitous today it’s easy to forget just how young it is. Computing as a commercial industry is barely 70 years old.

The World Wide Web, which ushered in the era of instantaneous digital communication that shapes so many services today, is, generationally speaking, a Millennial.

We are emerging from the sparky, experimental phase in which it seems possible that any task could be automated by anyone with a bit of skill. We are starting to have more probing conversations about the responsibilities designers of AI systems should bear, and what those systems should look like.

Regulatory reforms, both in Australia and overseas, are increasingly focused on influencing technology design and deployment, through lenses like data protection and privacy, right to repair, data sharing and procurement.

The European Union (EU), following on from the General Data Protection Regulation (which has influenced, directly and indirectly, data laws across the world), has proposed a draft AI Act, which seeks to set baseline standards for AI system design, deployment and interaction with humans in every sector across the EU.

It’s common to hear complaints about the ‘patchwork’ nature of technology and AI-related regulation. While inconsistencies and contradictions have long been part of law-making challenges, these complaints speak to a desire to neaten things up, to gather together fraying threads.

But when we look at the backdrop of other waves of technological innovation this patchwork effect not only makes sense, but is the sign of a deepening, and more distributed, landscape of expertise. Trying to pave over this only delays its growth. We are part way on a journey that will occupy our lives, our children’s lives and the lives of their offspring.

Considered this way, the increasing complexity of AI regulation is not to be fixed but to be faced head-on, requiring new professions and new expertise to cultivate it.

To create a safe and responsible AI future we need to think in systems

I work at the School of Cybernetics – the first school of cybernetics to be established anywhere in the world in nearly half a century.

Cybernetics is an old field of inquiry and a sprawling one, connecting scholars and practitioners across disciplines broadly interested in how information flows within and between purposeful systems: human, machine, animal and environmental.

It is part of a more systemic, interconnected way of making sense of the world that extends back to the very origins of human civilisation, most enduringly reflected in Indigenous knowledge systems.

Like AI today, cybernetics once preoccupied a range of academic and public discussions across continents. It inspired science fiction, art, manufacturing, new ways of thinking about how we organised information, labor, our families and our societies.

It was the wellspring from which a range of new disciplines emerged, like complexity science, systems engineering, design theory – and AI.

But while scholars under the umbrella of cybernetics had loosely sought to make sense of relationships and feedback loops between systems, as part of understanding and improving how those systems functioned, AI turned inwards, towards perfecting the automation of tasks using computers without concern for relationships between those automated tasks and the dynamic contexts in which they operated.

In doing so, over the last three quarters of a century, the tendrils of cybernetics – which sought to ensnare computers within these messy, dynamic contexts – were lopped away.

Today, notions of software as connected to and in relationship with humans and societies have re-emerged. The 21st century is being defined by complex, interrelated, systemic challenges: climate change, public health, automation, labor, education and radicalisation. Each discrete intervention forms part of a broader web of relationships, causes and effects.

Cybernetics gives us a way of stepping back and considering AI developments in terms of patterns and systems. Seen this way, the history of electricity tells us a great deal about the complex industries, standards and rules poised to unfold before us if AI is reframed as a constellation of many types of software, techniques and contexts, rather than one unified thing.

Take facial recognition, for example, as one cluster of technologies under the umbrella of AI. It is clear that this next decade will see a deepening and splintering of expertise, rules and requirements for facial recognition, depending on the kind of facial recognition used, who uses it and in what context. And this splintering won’t be an indicator of needless complexity, but a sign of deepening professionalism.

In early 2020, facial recognition company Clearview AI made headlines following revelations it had scraped over three billion photos from social media and public websites and sold the resulting facial recognition database to law enforcement agencies around the world. In Australia, news broke that the Australian Federal Police, and some state police forces, had been trialing the software.

Clearview AI was not the first or only software company selling facial recognition to law enforcement, but it was the most brazen. It openly flouted data protection rules in various countries to amass its enormous database and was publicly unabashed about harvesting people’s faces without their knowledge or consent.

There were also concerns its product was dodgy in other ways. The New York Times alleged Clearview AI retained the ability to monitor what its law enforcement users were searching for, and edit and remove results.

Distinguished Professor Genevieve Bell sums up one of the central ideas of cybernetics succinctly with the phrase: “the output of a system becomes its future input”.

Clearview AI’s original actions – illegal, outrageous, unapologetic – constrained its own future possibilities, spurring a raft of investigations of the company in various countries as well as moves to ban companies from purchasing its software. It also proved a tipping point for debate around facial recognition regulation more broadly, becoming an exemplar of all that was wrong in the field.

In May of this year, the UK Information Commissioner’s Office fined Clearview AI £7.5 million and ordered it to stop using any data from UK residents and delete that data from their systems. In Australia, the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner investigated and declared Clearview AI had breached national privacy rules. In the United States, Clearview AI has agreed to cease sales of its product to private companies and people, but continues to offer it to law enforcement and government agencies.

The story of Clearview AI isn’t just one of regulatory intervention in facial recognition. Stepping back, it tells us that the design and deployment of facial recognition will slowly change – not in one sudden bang, but in a series of interventions from different players at different speeds.

Markers of ‘quality’ or ‘verifiability’ for datasets used in high stakes contexts will emerge. An increasing focus in the research community today on dataset audits, provenance improvements and dataset ‘fingerprinting’ will eventually shape commercial products.

New business models will emerge – public and private – for things like facial recognition software certification and quality assurance, as well as curating and licensing high-quality data it draws from. And, these new rules and businesses and techniques will eventually vary from context to context, depending on whether facial recognition is being used for law enforcement, or for commercial security, or in private spaces.

In some contexts – for example in schools and universities, where it is currently being trialed to monitor lunch purchases and exam proctoring – my own hope is that facial recognition will ultimately be banned altogether.

Change will come unevenly, iteratively and distributed across a broader system of regulation and expertise. The evolution of other complex systems tells us that this is part of the process of making things trusted and safe to use. You cannot electrify a hospital using the same methods as wiring up a residential house, and electrifying a hospital is not the same as electrifying trains or cars. Different contexts necessitate different skills and language and requirements.

This realisation – that the future we are facing will be more complex and require greater specialisation – is an opportunity to recast narratives in Australia of innovation progress.

Rather than thinking of safe, sustainable AI only in terms of regulatory interventions, we can recognise and invest in the enabling systems – new businesses, innovative techniques and methods, new jobs and forms of certification – that will make this future a reality.

So how do we do this in practice? We can expand existing grant schemes for new and novel technologies with funding specifically for research and applications that promote safety, standardisation, and verifiability of AI systems.

Funding drives research and industry focus, and influences what is valued. We could target high-stakes contexts where the potential for harm from poorly designed or misused technologies – like facial recognition – as priority investment areas.

To increase the legibility and robustness of new technologies for government, we could take the best bits of technology assessment agency models, like the US Office of Technology Assessments and adapt them for an Australian context.

And we can continue to expand education programs embedded in real-world contexts that are designed to equip people managing new technologies with a clear sense of the systems and contexts they operate in, supported by tools and techniques to help them manage this complexity.

The School of Cybernetics, for example, is the first in Australia explicitly focused on using cybernetics and systems methods to reimagine new technologies, through both building and analysing systems, with micro and macro education programs purposefully connecting with and using case studies from industry and government partners.

AI prevents us from talking about what actually concerns us

In March the US-based Center on Privacy & Technology announced it would no longer be using the phrases artificial intelligence, AI or machine learning in its work, saying the terms had become placeholders for more scrupulous descriptions that would make the technologies they refer to transparent and graspable for everyday people.

Whatever the original scientific aspirations of AI, executive director Emily Tucker wrote, the term has primarily come to “obfuscate, alienate and glamorise” a range of practices and products.

Language matters. Gathering together a host of different technologies, made for different purposes and contexts, under one term prevents us from being able to articulate our specific concerns and take action on the pieces that matter most right now.

We could spend the next decade lost in definitional debates about AI, for the purpose of regulating or constraining ‘it’. We could entertain years of objections about how low-risk activities would get swept up in efforts to regulate a few bad actors in high-risk settings, because we are reluctant to let go of AI as a discrete industry, its limits to be defined by an elite few. These debates would only serve those who benefit from inaction.

Or we could get specific in our intentions, and purposeful in how we use language to give life to those intentions. These issues are not simple. They deserve attention. The world is complex – and getting more so.

The perfect solution won’t be a simple rulebook, covering our entire society – it will be complex, reflecting the society it seeks to shape. It will be iterative, diverse and embrace complexity. And it will aim to build a robust, distributed and multilayered system of regulation and expertise.

This is what we are good at, us humans. It is the wave we have ridden with each fresh technological disruption. So, when it comes to ‘regulating AI’, we shouldn’t let the false perfection of simplicity and unity be the enemy of the good: the messy, ongoing and partial reality of progress.

Professor Ellen Broad is an Associate Professor with the School of Cybernetics, founded by Distinguished Professor Genevieve Bell at the Australian National University, where she focuses on designing responsible, ethical and sustainable artificial intelligence (AI). Ellen has spent more than a decade working in the technology sector in Australia, the UK and Europe, in leadership roles spanning engineering, data standards development and policy for organisations including CSIRO’s Data61, the Open Data Institute in the UK and as an adviser to UK Cabinet Minister Elizabeth Truss.

Do you know more? Contact James Riley via Email.

Optimistic and naive.