The University Research Commercialisation Action Plan has been developed by the Department of Education, Skills and Employment. However, in a case of ‘if all you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail’, the action plan fails to address the whole issue.

The University Research Commercialisation Action Plan is a policy that starts from flawed premises. The first is the fallacy of the linear model. The second fallacy is to regard this as a problem with how to run our University sector.

An example of this second fallacy is the Australian Chamber of Commerce and Industry submission quoted in the URC Action Plan. They place the blame for lack of industry-university collaboration on academic staff, writing:

“Currently the reward system inside universities is not set up for commercialisation or collaboration with business. Researchers focus on academic publications as the primary output of their research since they are not incentivised to consider commercial application.”

While Universities do a lot of research, they are first and foremost higher education institutions. They exist to teach subjects that should be taught by active researchers. Therefore, it is appropriate that University research focuses on academic publication.

Firstly, academic research publication is part of the ecosystem that develops the public good of knowledge. Secondly, academic publication is the process of validation and verification of research.

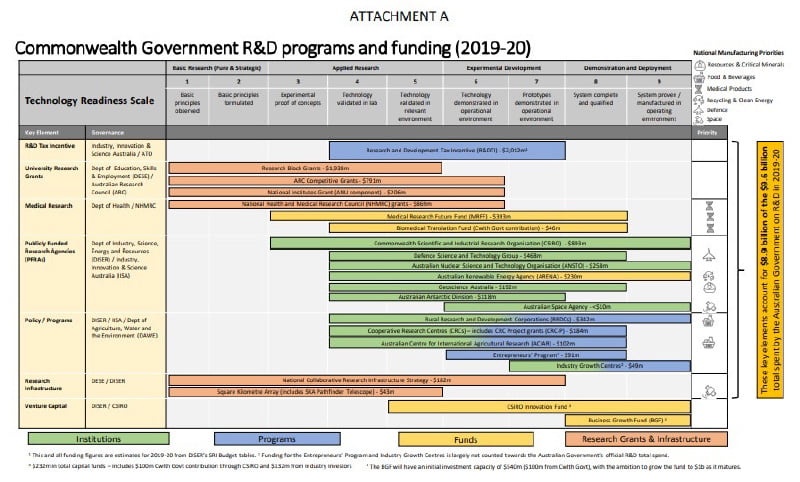

The submissions from the Business Council of Australia and AusBiotech called out that other important aspects belong in the departments of Health, Defence and Industry. The BCA, in particular, provided an excellent diagram summarising the Australian R&D system.

But apart from calling for a ‘whole of government’ approach, they provided little analysis of the issues on the industry side. Partly this stems from the focus on equating research commercialisation with startups.

But it ignores the issue of Australia fundamentally being a branch economy and the tendency of the multinational players in Australia to prefer to do research elsewhere. Moreover, R&D tax concessions to multinationals who barely pay any tax are also highly ineffective.

The Action Plan has a fixation on questions about the skills and experience of academics and business executives to engage with each other, writing:

“In the same way many university researchers lack the skills and experience to engage with business and industry, many of those in business also have a skill gap in their capacity to engage with universities and take advantage of the opportunities presented by research and innovation. For industry, the complexity of university structures and protocols can make finding a point of entry and navigating the system a challenge.”

The core issue isn’t the lack of skills or experience in engaging; it is that business in Australia sees little need to engage.

There is no shortage of executives that believe Australia’s role on the planet is to be a technology taker. Pushing Universities and their staff to pester business will not improve the situation.

The new funding in the Reform Agenda isn’t for research. The $1.6 Billion over 11 years to establish Australia’s Economic Accelerator – a new stage-gated program dedicated to funding translation and commercialisation in priority areas.

That is, it only flows to a research project that fits the linear model, and it funds the commercialisation process, not the research itself.

The Reform Agenda also includes adjusting $2 billion in existing university research funding to incentivise commercialisation better.

The first element of this is changes that have already occurred supposedly to Strengthen Australian Research Council arrangements in the national interest. Astute readers will note that ‘the national interest’ was the basis on which Minister Robert decided to reject some ARC funding proposals. This is just a strengthening of the concept of an authoritarian government knowing how to drive a research agenda.

Another element of this adjustment is changing the Research Block Grant funding to increase the allocation to a university for its increased generation of industry funding and to change researcher remuneration. That is, for university researchers to spend more time pestering industry for money.

The Department of Industry’s Modern Manufacturing Strategy had ‘Make Science and Technology Work for Industry’ as one of its pillars, which included aligning research capabilities and programs to the priority areas. That is what the CUR Action Plan notionally delivers.

The question that remains unanswered is the motivation for Australian industry in increased research and development spending. Listed companies have developed an excessively short-term focus, with more attention on quarterly earnings than future opportunities.

This has been compounded by changes to superannuation laws to focus super investors on the short term return of their funds.

The Modern Manufacturing Strategy had a one-line entry under the pillar of Getting the Economic Conditions Right for Business of ‘Building management capability.’ Yet the only action for that seemed to be the Global Business and Talent Attraction Taskforce.

Perhaps now that the Education department has finished its task of lecturing universities on how they need to do things with business, the Industry department can revisit its strategy.

They need to work out how to get businesses to invest in R&D at all and how to get them to value the skills and capabilities that Universities can offer.

While they are at it, they could remind businesses and the Department of Education that the bulk of the innovations that constituted Apple’s launch of the iPhone came from the social sciences and humanities.

As an example, the current most significant development requirement in renewable energy is building smart energy systems that households will adopt.

This is the second column on this subject in a two part series. You can read the first article here.

David Havyatt is a former telco executive, former adviser to Federal Labor Ministers and advocate on behalf of energy consumers. He is a long term observer of Australian innovation policy.

Do you know more? Contact James Riley via Email.

A very interesting international perspective here https://www.timeshighereducation.com/depth/chasing-unicorns-best-commercialisation-strategy (you need to register to read – I don’t think it costs).

Great article and comments. This is frustrating topic for the reasons expressed, especially by Andrew McCredie. A major missing part of the policies is that it is “people”. Collaborations and problem solving is effected by people, and yet the people bit hardly gets a mention. You may be in Industry or Academia – but in the end, “someone” has to pull teams together from both sides to solve problems. Engineers and researchers in Australia are fantastic at solving problems, but someone has to phrase and communicate the problem that needs to be solved, be it an innovation step or a new product.

Yes it is very sad to see a misunderstanding of the innovation process driving the new influx of innovation funds (after years of cuts).

The Federal Department of Industry and innovation knows this very well, which is probably why it has passed the bulk of the funding to the Education Department.

It almost seems as if the Government (and their consultant advisers) have read the worst caricature from the 1980s Friedmanites on the folly of Government funding of innovation/industry policy and implemented that model.

Universities are very good at identifying and developing ideas, some of which turn out to be really important, and they have a variety of systems that do a reasonably good job at directing funds for that purpose. Innovative businesses have a good understanding of how to get new ideas to market and government funding to encourage that has a reasonable track record of success.

Creating a Frankenstein mixture of the two and expecting the best to emerge is to put faith before wisdom.

It seems unlikely that universities overseen by a government committee and in some sort of partnership with businesses will suddenly develop lots of commercialisation pathways just because there is a lot of money around. Friedman would predict that all that will happen is that a lot of people will waste their time trying to get their hands on the money.

Unless you are doing innovation for a global market, your competitors who have access to global markets will be able to massively outspend you, and you have to be very clever to beat that. There are only a few Australian companies with this access, most notably CSL and BHP and they are most active in trawling the research in their fields of interest, not just Australian universities, universities around the world.

An innovation funding model that has no understanding of the pathway to market of innovation can only lead to heartache and frustration.

Great series of articles David you certainly highlight the key things researchers, business and government need to think about and hopefully change their role in this essential tripartite collaboration. I all my interactions with the three sectors is see two fundament issues that need resolution.

1. Researchers should stop pestering industry and start engaging industry to identify real world problems that will make them better and more successful researchers.

2. Business needs to stop seeing R&D tax credits as a tax rort and recognise that Australian businesses need to be globally competitive based upon solutions that solve extremely difficult problems that they can solve by collaborating with our world class researchers. Science commercialisation will then flow (in dynamic and non linear ways) and all government has to do is get the incentives right and get out of the way!